In this short essay, I intend to discuss the meaning and interrelation of the senses of Scripture. Once we have analyzed the nature of and distinction between these different senses, we will then explore how this meaning and interrelation provides the foundation for an interpretative stance or hermeneutic in a Catholic context. We will begin by presenting a precise definition of what we refer to as the “literal sense” of Sacred Scripture, and this will be followed by an examination of the technical meaning of the “spiritual sense” of Scripture as the Old Testament is read in light of the paschal mystery revealed in the person and work of Jesus Christ. Next, I will present the fourfold division of this spiritual sense with a concise and popular example. Then, after briefly considering a more general understanding of the spiritual sense, I shall present the thought of Ignace de la Potterie, S.J. regarding the relationship between the sacred writer, the reader, and the interpreter and their shared experience in the one Spirit as each perform their respective roles of writing, reading, and interpreting.

The historical-critical method of interpreting Scripture aims at determining the meaning of the inspired Biblical text as it was originally expressed by the inspired human author. Dei Verbum informs us that “the interpreter of sacred Scriptures, if he is to ascertain what God has wished to communicate to us, should carefully search out the meaning which the sacred writers really had in mind” (DV 12 § 1). Whether the original authors spoke in narrative, metaphor, hyperbole, etc., what they intended to communicate on the historical and literal level is that sense which we term as “literal”. This literal sense is not to be confused with a literalist rendering of the text, which is popular in fundamentalist circles, fails to account for the fact that God’s Word is couched in human language by human authors in time-conditioned human language and phraseology, and neglects the literary genres and modes of human thought.

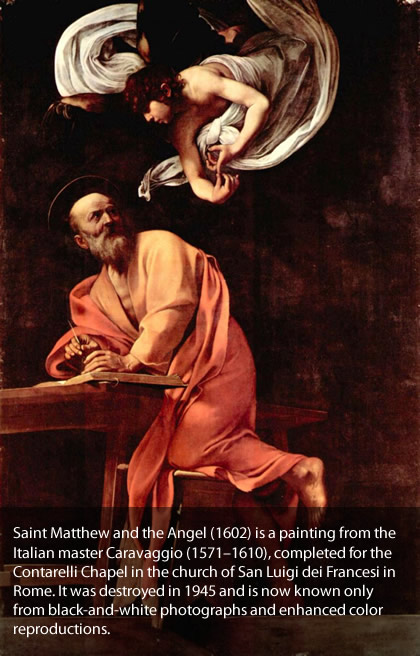

In his encyclical letter Divino Afflante Spiritu, Pope Pius XII reminds us that “what was said and done in the Old Testament was ordained and disposed by God with such consummate wisdom, that things past prefigured in a spiritual way those that were to come under the new dispensation of grace” (DAS 26). Put otherwise, God writes history like men write words. The people, things, places, and events of old have, in the ineffable providence of God, come to be seen as pointing to the realities of the New Covenant as seen through the lens of the paschal mystery, fulfilled in the person and work of Jesus Christ. St. Augustine of Hippo provides us with a concise explanation of this reality when he writes, “In the Old the New lies hidden, and in the New the Old is unfolded.” Dei Verbum, the Second Vatican Council’s Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation, explains how “although Christ founded the New Covenant in his blood, still the books of the Old Testament, all of them caught up into the Gospel message, attain and show forth their full meaning in the New Testament and, in their turn, shed light on it and explain it” (DV 16). This Christian understanding of the Old Testament therefore constitutes an added spiritual sense upon the literal sense of Sacred Scripture.

The Pontifical Biblical Commission, in its document The Interpretation of the Bible in the Church, tells us that “the paschal event, the death and resurrection of Jesus, has established a radically new historical context, which sheds fresh light upon the ancient texts and causes them to undergo a change in meaning” (IBC, p. 84). This “change in meaning” constitutes a movement from the literal sense of these ancient texts to the spiritual sense as understood in the light of the Christian faith. St. Paul demonstrates this spiritual reading of the Old Testament through a Christological lens when he writes that Adam “was a type of the one who was to come” (Rom 5:14). The author of the Letter to the Hebrews tells us that “the law has but a shadow of the good things to come” (Heb 10:1). We may even go further and say that “when a biblical text relates directly to the paschal mystery of Christ or to the new life which results from it, its literal sense is already a spiritual sense” (IBC, p. 85). So in the New Testament, we are able to directly witness this spiritual sense when we ascertaining the literal sense.

Joseph A. Fitzmyer, S.J. explains in his Scripture, The Soul of Theology that “in the Middle Ages, as a heritage of the patristic period, the spiritual or mystical sense was not only distinguished from the literal but subdivided into three forms: the allegorical, the moral (or tropological), and the anagogic (or eschatological) senses” (Fitzmyer, p. 67). The literal sense teaches facts; the allegorical sense instructs us in what we are to believe; the moral sense informs us of Gospel morality; and the anagogic sense describes that which we are to hope for. This fourfold division of the senses of Scripture is also popularly referred to as the Quadriga. As an example of this, the Solomonic Temple was a structure that existed in space and time in the Davidic Kingdom, built as it was upon the rock of foundation in Jerusalem. This temple points allegorically to the Christian’s body, which houses the indwelling presence of God. Due to this allegorical reading informed by the paschal mystery, we now understand that we should treat our Christian bodies with great respect as we should keep from defiling this new temple (Cf. 1 Cor 3:16-17). Thirdly, the temple points to the eschatological reality of heaven, which is the destination of our Christian hope. With all of this in mind, in his Summa Theologiae, St. Thomas Aquinas maintained that “all the senses are based on one, namely the literal” (ST 1, q.1, a.10) As we spiritually read the Bible in the light of Christ, we need to recognize that “the spiritual sense can never be stripped of its connection with the literal sense,” which remains “the indispensable foundation” (IBC, p. 85). We should avoid confusing the spiritual sense with all type of subjective interpretations that stem from the imagination or intellectual speculation.

Thus far, we have reviewed the Sensus Spiritualis in its technical understanding. However, there is a second and more general understanding of the spiritual sense that is more complex. This is a living sense wherein the Scriptures have a living meaning that allows for a personal appropriation of meaning in the life of the believer. “As the reader matures in the life of the Spirit, so there grows also his or her capacity to understand the realities of which the Bible speaks” (IBC, p. 80). When the reader is immersed in the life of the Spirit, the reader participates in those realities that the Biblical text speaks of. Now, with this new life in the Spirit, the reader receives the text within the context of this new life mediated through Christ.

Ignace de la Potterie, S.J. explains that the Spirit exercises a true causality on the sacred writer, the reader, and the interpreter of the Scriptures, and this causality therefore determines the manner in which these three subjects carry out their respective activities. Due to the causality of the Spirit through his action on the sacred writer, the actual text of the Scripture receives an indwelling of the Spirit. For that reason, the inspired text must then be read and interpreted in the Spirit. The three agents are all moved by the same Spirit, and so they share in common this same Spirit. Though each of these subjects live in different centuries and cultures, this shared Spirit dwells in each for the accomplishment of their respective tasks. This common sharing in the one Spirit between the writer of old and the interpreter of today allows for the creation of a deep communion, a mysterious unity that rises above the barriers of culture and unites them. The inspired texts themselves possess two dimensions: the exterior and the interior. The exterior dimension is the quality of being texts that are written at a particular time in a certain language, and so are subject to philological, literary, and historical studies. The interior dimension involves the texts’ relationship to the Holy Spirit wherein they contain an underlying “sense” whereby they reveal the salvific plan of God because they have in them the very presence of the Spirit.

Potterie builds upon this principle that “one must read and interpret the Holy Scripture in the same Spirit with which it was written” (DV 12 § 3). In doing so, Potterie speaks of the subjective and objective aspects of this principle. The subjective aspect is concerned with the interpreter; the interpretation of Scripture in the Spirit is not possible except in the light of faith. He notes that in order to understand Scripture spiritually, the believer must participate in the Church’s movement of conversion. St. Jerome explains that only the spiritual man can discover Christ in the divine texts, and St. Gregory asserts that if one has not received the Holy Spirit of God, he cannot in any way understand the words of God. The objective aspect deals with the Spirit that resides in the inspired Scriptures. This reality is separate from the subject, the interpreter; therefore he employs the term “subjective”. Due to the action of the Spirit in the writing of the biblical text, the text becomes Holy Scripture, the Word of God, and so the texts of Scripture possess a dimension of interiority that secular texts lack. The inspired Biblical accounts include a “spiritual sense” that is the result of the presence of the Spirit in the letter. Therefore, the challenge for Biblical interpretation is to discover the Spirit in the letter through the cooperation of the interpreter with the Spirit and then extracting the underlying spiritual meaning of the Scriptures. Interpretation must reach deeper than just the surface of the objective text. This is a seeking out and making explicit of what is only implicit in Sacred Scripture. This approach championed by the Fathers of the Church and brought to the fore by Potterie challenges an approach that clings only to the literal sense derived from the historical-critical method. The scientific mind would recognize only that unveiled by the historical-critical method, whereas the faith perspective of the believer would recognize the different spiritual senses as authentic alongside the literal sense.

The Second Vatican Council, in Dei Verbum, hands exegetes three practical means for the Christian interpretation of Scripture. First, we must allow for a canonical reading of the Scriptures by remaining attentive to the unity and content. This includes allowing recognizing and revealing the intertextual echoes throughout the Bible. This method follows St. Augustine’s principle that we should explain the New Testament in light of the Old and the Old in the perspective of the New and acknowledge that the main purpose of the Old Testament was to “prepare for and declare in prophecy the coming of Christ” and “indicate it by means of different types” (DV 15). Second, exegesis is a work of the entire Church and not merely an academic process, so we should give attention to the living Tradition of the whole Church. This is a call to maintain the unity and continuity between present-day exegesis and patristic exegesis. True Christian interpretation cannot be carried out except in a living continuity with the Tradition of the Church. Finally, our interpretation should be normed by the analogy of faith whereby our interpretation should rest in harmony with the whole Christian faith.

Following the ancient Patristic tradition, the spiritual sense is dependent upon the literal as its foundation. Like a signpost, the literal sense provides a magisterial role for any further spiritual reading of the text as the interpreter, illuminated by the same Spirit that inspired the sacred author, draws out that deeper meaning intended by God in light of the paschal mystery. While the literal is foundational for the spiritual, the spiritual sense complements and completes the literal sense for the reason that the literal fails to go the distance in communicating what could be said in the act of interpretation. In ascertaining that sense resulting from the indwelling presence of the Spirit in the sacred text, the form of exegesis being performed is uniquely “Christian”. Consequently, the exegete who wishes to approach the Word of God to mine it of its full meaning apart from an impoverished and solely secular approach needs to immerse him/herself in the life of the Spirit by entering into that faith perspective informed by the same Spirit who inspired the sacred authors and now indwells the sacred letter.

We began with a clear definition of the literal sense of Sacred Scripture and moved from this point of departure to a consideration of what exactly the spiritual sense of Scripture is from a Christian point of view, especially as it has been further divided in the tradition of the Church into the allegorical, moral, and anagogical senses. We then explored Potterie’s depiction of the unity today’s contemporary “Christian” exegete shares with the sacred author – a unity grounded in the same Spirit of God – after considering a general definition of the spiritual sense. In conclusion, we may recognize that a Catholic interpretation of Sacred Scripture must consider the full depth of Scripture as the Word of God illuminated as it is by faith and grounded in the intentions of the original, human writers through whom the Spirit principally authored the Biblical record.

Carson Weber, the author of the above essay, has provided a free 30-episode podcast online titled "The Understanding the Scriptures Podcast" which takes his listeners through the entire bible from Genesis to Revelation.