No doubt many of us were disappointed about the decision that the Supreme Court reached upon the legality of same-sex marriage. Some may say, 'well it was only a legal decision that affects not the Church.' While this is in some sense true, the state nevertheless empowers Catholic clergy with state prerogatives to minister and witness weddings, thus recognizing them as legitimate contracts with the state. In that way then, it would be erroneous to say it affects us not. By this decision, so long as clergy remained empowered by the state, Christian matrimony may fall under legal attack by all those who would see it further made into the image of the age. It may be necessary at this time, to separate Christian marriage from civil recognition to avoid further complications, however that may require its own separate treatment.

The destruction of Holy Matrimony did not start with the homosexual lobby. Traditionally it has been dated to the sexual revoution of the ninteen sixties, or further back with the adoption of contraception in the ninteen thirties by Protestants. However, if we look beyond the twentieth century, we see its roots reach further back. Since the Christianitization of Europe, Christian matrimony was seen as a lasting covenant between a man and woman united in Christ to form what Saint Augustine of Hippo called a "little trinity". Husband and wife were united to compliment to one another, welded together by the love that sprang forth from the Holy Spirit present in both of them: 'Flesh of my flesh, bone of my bones". (Gen 2:23). So where there were two, there were now three, as each one spouse is charged with acquiring the Holy Spirit (Acts 19:6).

Our contemporary marriage problem starts not in San Francisco, but in the most ancient of places: Rome. In Late Antique Rome, secular law had been brought into the service of Christianity by numerous emperors (Theodosius, Justinian), and to the Romans (who were the Byzantines), the great legal tradition they inherited was a source of pride and assurance of their exalted place amongst the people's of the world. It was after all, the law of Rome that had been brought to the barbarian lands of Europe and had raised them out of bronze age. Thus the cult of the state still remained (which had flourished in the pre-christian times), however subdued it may have been, and from time to time it became a source of tension with the Church. Divorce and remarriage was one such issue.

In Roman antiquity, marriage was sustained by the continued desire of both partners. If by mutual consent or some infraction caused by one spouse, the marriage could be dissolved in the eyes of the state. Both partners were now free to remarry whomever they'd liked. This legal view of marriage continued until Justinian's reign in the 6th century. However many faults Justinian had, he seemed to genuinely desire to better society, and sought to do this by updating civil law to bring it into accordance with Christian teaching. Where in centuries past, the great Church Fathers of the first few centuries had exhorted the faithful to a pious life by their own piety and preaching, Justinian would go further and legislate Christian morality to his people.

Among his reforms were those concerning marriage. No doubt his passionate love for his wife Theodora influenced his views on marriage (He never remarried after her death, and was forever broken at her passing). Justinian championed outlawing divorce completely from Roman law. This was met with protest by many prominent Constantinopolitans, including a good many jurists. Unable to have this revision adopted, Justinian opted for a restriction on the causes for divorce, so that no-fault, or mutual consent as was tradition for eons in the Roman Empire, ceased. Nevertheless, the civil law of the Roman Empire continued to run parallel (as civil and religious law do today in America) to ecclesiastical law. The Church would now become an extension of the imperial office, and continue on this close path of church-state relations that reach its climax in the middle ages.

The Christian tradition however, was that one who had divorced his spouse, or had separated for some reason, would have to remain celibate; a continent marriage so to speak. Remarriage, except for certain circumstances was not permitted. Often times men and woman who no longer could reconcile their marriage would enter a monastery, pledge themselves as eunichs, or simply live a celibate single life in the Roman milieu. This would change in the 8th century, as Church teaching came to head with secular power and the passions of one man.

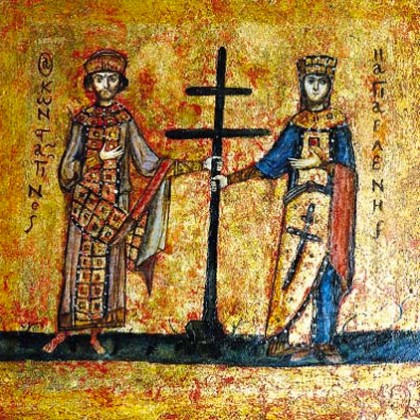

That man was Constantine VI, a secret Iconoclast, whose mother Irene had been in his estimation an overbearing regent. Whatever the case, when he came of age and ruled in his own right, he sought to make his own mark in history. Dissatisfied with the arranged marriage he had with his wife Mary, he sought to legitimize his adulterous affair with Theodote, a hand-maid to Mary (Henry VIII much?). Constantine sent Mary away to a convent and arranged to have his two daughters by her taken care of away from public light. With this all in order, Constantine VI approached the Church with his desire to wed Theodote.

There he hit a wall. The Patriarch of Constantinople, Tarasios, was an Iconodule (one who loves icons). It was Irene, Constantine VI's mother, who had helped convoke (in Constantine's name of course) the Seventh Ecumenical Council in Nicea, which upheld the veneration of religious images and icons. Constiantine VI, who had signed the decrees of the council, while not rejecting their decisions, also held sympathy with the Iconoclasts and their positions. Patriarch Tarasios flatly refused to marry Constantine and Theodote. The Church was firm in its teaching that marriage was the union of two people, and any practical dissolution in the relationship did not affect the mystery at work in their lives. Though questionable cases of remarriage had happened in the past, remarriage after divorce was not normative.

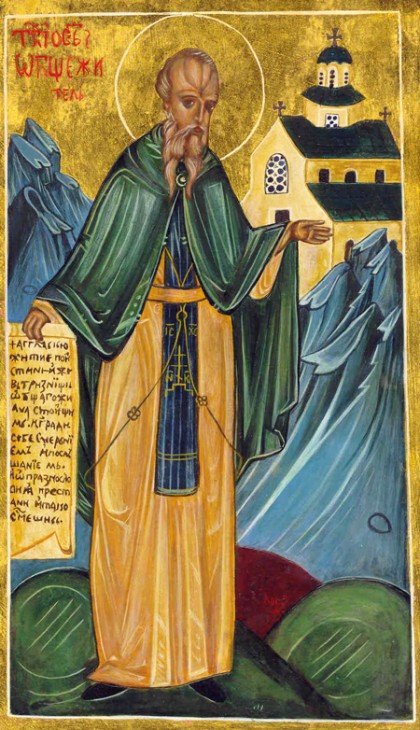

Constantine pushed ahead, and the Church in Constantinople became embroiled in what is known as the "Adultery Controversy". The Studite monks, led by the vocal St. Theodore, opposed the marriage and endeavored to protest visibly in the city, whipping up popular support. Initially Constantine VI was dismayed, but he pressed forward, courting the suffragin bishops of the region with lavish dinners and promises of future power. Constantine also played to popular conceptions of love and romance to woo the aristocracy. As the controversy began to ebb, the Studites, who were staunch iconodules and held much influence due to their Orthodoxy, stepped up their game, refusing communion with any cleric who supported the remarriage. The pressure was on Patriarch Tarasios and he finally relented, appointing a priest to celebrate the wedding in his stead. Ashamed, he locked himself away in his chancery for the duration of the festivities. The Studites resolved to continue their protest, refusing communion with Tarasios. Even after the controversy waned from the public square, and the Emperor lived out his days "married" to his wife, the Studites remained steadfast in their opposition, a very big thorn in the Emperor's side. The Studites continued their protest even into the pontificate of Tarasios' successor. When the Emperor finally reposed, St. Theodore and his monks refused communion with the next Emperor if he did not repudiate the actions of Constantine VI. The new Emperor, Michael I, wanted peace in the city, so he wrote to the Pope explaning the situation. He obtained for Theodore and his monks a letter from Pope Leo III that recognized the orthodoxy of the Studite monks, and decreed the dead emperor's actions reprehensible. With papal recognition of their cause, the new Emperor Michael I made Theodore his personal confessor and did much to support the monastery of studios during his reign.

While Constantine's remarriage received papal condemnation, the marital controversy begun by Constantine would leave a lasting legacy. As civic law and ecclesiastical law continued to run parallel to one another, this somewhat contradictory arrangement would be further complicated by Emperor Leo VI's decree in the tenth century; that the only valid marriages in the Byzantine Empire, were those made in the Church. A century later, the Byzantine Church would enter into a period of off-and-on communion with the Catholic Church, until becoming irreparably separated in the 15th century. During this period, the legal ramifications of remarriage and divorce, through the blending of civil and ecclesiastical law became apart of Byzantine spiritual practice. The list of what constituted acceptable reasons for divorce also increased, so that any couple could in effect find some legal reason (and as such, an ecclesial reason), to divorce. As divorce became more common, so too was the laxity on remarriage. Eventually, it became so prevalent, that it was necessary to restrict remarriages to two. So complete was this redefinition of Holy Matrimony that in the 18th century, long after the death of the Byzantine Empire, the canonist and compiler of the Philokalia, St. Nikephoros of the Holy Mountain would comment on the number of remarriages permitted in Orthodox canon law, including the reasons one could recieve a Church sanctioned divorce. While countless Orthodox saints have expressed and exhorted the married faithful to remain virtuous and committed, there nevertheless is the acknowledged acceptance that such a union that their forefathers believed was eternal and binding, could be undone and remade with new persons, as simply as cutting rope and tying another piece in its place.

But this isn't a polemic against the Orthodox Church, rather it is to show how deep the roots of our current battle go. But even so, we cannot throw up our hands in the air and let each new redefinition go uncontested. We must take heart in the long and difficult fight the Studite monks took part in, even when the controversy became passé. By looking into our past, and learning from our history, we can avoid despairing, seeing how God vindicates the patient and the faithful.

Gay marriage (If we can even call it that) was made possible by our acceptance of divorce and remarriage. We have failed as Catholic community in a Protestant majority country to change the culture and in failing to do so, prevent the change in US law in 1969 allowing for mutual consent divorce. We also failed to catechize properly our own faithful on the mystery of marriage in the face of wider societal change.

It seems rather fitting that our story should have occurred in the midst of the Iconoclast period. Pope Francis, in speaking about the mystery of marriage calls it an "Icon of God's love for us." He goes on to say that "the image of God is a married couple, man and woman, not only man, not only woman, but rather both." Pope Francis says "we were created to love, as a reflection of God and his love. And in matrimonial union the man and woman realize this vocation, as a sign of reciprocity and the full and definitive communion of life" . Like the holy icons, which the Iconodules defended, marriage shows us something about the nature of God. That he became one of us, because he Loves us. And in loving us, he hopes that will in turn love him, and one another, with that same burning love he showed us first. That is the same fire which a man ought to show for his wife, and which a wife ought to have for her husband. This is how we become 'Icons' of God's love to one another.

We live in a period of new iconoclasm, where the icon of marriage like the holy images of the 8th century are seen as blasphemous to the religion of the age; secularism. So like the iconoclasts who defaced, tore down, and burned icons, so the secularists are doing the same to the icon of marriage. Not only by calling it unfashionable; but also by corrupting it, by changing it so that it now longer shows us (and the world) the love of God for his children.

Let us my friends oppose charitably, but boldy, as St. Theodore the Studite and his monks did, the attempts of the age to change what is good, and right, and beautiful. For as St. Paul wrote to his beloved disciple Timothy: "Everything that God has created is good, and we should not reject any of it but receive it all with thanksgiving." (1 Timothy 4:4).